(AGENPARL) - Roma, 22 Gennaio 2024

(AGENPARL) - Roma, 22 Gennaio 2024[lid] New Dinosaur Footprints in Lazio Region (Central Italy): A New Discovery?

“I was on a mountain trek with my 12 years old twin girls. We decided to take a rest on a calcareous block sticking out of the ground and, immediately, I noticed some unique marks on it. In certain geomorphological contexts, such as those of the Apennines, natural marks having a non-biological origin might resemble, morphologically, dinosaur footprints. However, I have walked across these mountains for almost three decades and never came across to something like this” says Dario Novellino, an Italian social anthropologist from Formia (Latina Province), with a personal interest in palaeontology. On the day of the first appraisal, he was able to detect 21 unique variably preserved marks, in addition to several unclear traces. Says Novellino, “this putative ichnological material might consist of footprints of presumably medium size quadrupeds and tetradactyl/tridactyl bipedal trackmakers, but – of course – only a professional palaeontologist would be able to confirm this”. On further recognisances to the area, Novellino also acquired more detailed information and measurements of these unusual marks, while he was able to identify new ones on two different track-bearing blocks.

The Area and its Geological Setting

The Aurunci and Ausoni mountains, in Central Italy, constitute the most landward portion of the Latium-Abruzzi Carbonate Platform. However, according to Novellino: “when different dinosaur species thrived around these areas, the Aurunci range did not exist. Here, instead, there was a tropical environment, probably characterized by wetlands with huge lagoons, islets and land bridges connecting various emerging territories. What is now solid rock was, then, a kind of limestone mud. So, the heavy footsteps of the dinosaurs were left impressed in the mud. Perhaps, the presence of a ‘carpet’ of microscopic algae served to guarantee some degree of stability to the surface where footprints were found. These were covered by layers of fresh sediments that hardened, overtime, thus creating fossil footprints”.

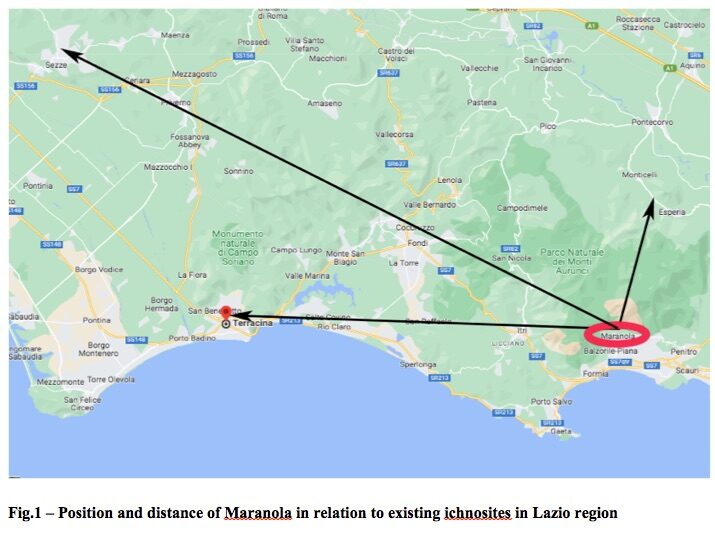

The investigated site in Maranola (Formia) is located at an altitude between 400-496 meters ASL and at about 15 kilometre away, as the crow flies, from the well known Esperia ichnosite in the western Aurunci Mountains and 60 km in beeline from ‘Cava Petraianni’ ichnosite, on the western ridges of the Lepini Mountains, near Sezze [figure 1]. It also distances at about 33 km, as the crow flies, from a quarrying site in the Ausoni Mountains, near Terracina, where a track-bearing block was excavated. According to Italian Palaeontologist Paolo Citton and some of his colleagues: “in central and southern Italy, the dinosaur track record covers a time span from the Late Jurassic to the Late Cretaceous and is related to shallow water carbonate successions pertaining to two different palaeogeographic domains: the Apenninic Carbonate Platform (i.e. Latium-Abruzzi and Campania platforms) and the Apulian Platform”. In this context, the newly discovered Maranola site fits, geologically, within the ‘Lepini-Ausoni-Aurunci Unit’. Interestingly enough, almost two decades ago, Italian well-known palaeontologist, Umberto Nicosia, whileillustrating the genesis of the Apennine ridge during a conference, he had already anticipatedthe possibility of finding dinosaur footprints in the Lepini-Ausoni-Aurunci mountains. If the putative footprints identified by Novellino would be found to be contemporary to those of the neighbouring Esperia site, then these could be dated between 120 to 140 million years ago, a period corresponding to the lower Cretaceous.

Preliminary Methodology

Novellino explains that the main morphometric parameters considered during his field appraisals were footprint length (FL), footprint width (FW), footprint depth (FD), distance and orientation of footprints. With reference to seemingly tetradactyl footprints, when details were discernable, the interdigital angles were computed and compared. Metatarsal impressions length (the elongated and narrow portion of the track, which terminates before the footprint widens distally) were also measured – when present. Each footprint was identified alphabetically with a letter; GPS measures and the altitude of the-track bearing blocks were also taken. Photographic images were acquired and later elaborated on computer using ‘photoshop’ software. Selected literature was also consulted, in the attempt of comparing the discovered putative dinosaur tracks with already identified footprint morphotypes of theraphods, ornithopods and sauropods.

Current Ichonological Findings

The first calcareous block identified by Novellino measures approximately 4,5 meters at its widest and 6,80 meters in its total length. Parts of the superficial layers of the block formation (especially on its lower portion) have been subject – most probably – to diagenetic and tectonic cleavage processes, as well to seasonal summer fires over long periods, causing the removal of portions of the superficial layers, hence making difficult to identify any particular mark [figure 2]. All tracks are generally scattered and, some of them, are weakly impressed, perhaps due to differences in water content on distinct portions of the original track-bearing surface. As of now, only the most visible traces in natural light, have been reproduced by photographs; amongst these, there are at least 12 unique variably preserved marks and other unclear traces. Majority of footprints are oriented N-NW and N-NE. According to Novellino: “it might be possible that the existing tracks might be associated with small to medium-sized theropod, sauropod and perhaps ornithophod dinosaurs”. Theropod dinosaurs [figure 3] were mostly carnivorous and generally bipedal. The shape of their pelvis was very similar to that of modern birds. They had a fairly small but robust skull, with large nostrils and numerous sharp teeth. Instead, sauropods [figure 4] were fully herbivorous, they had very long tails and necks and a small head, if compared to the rest of the body.

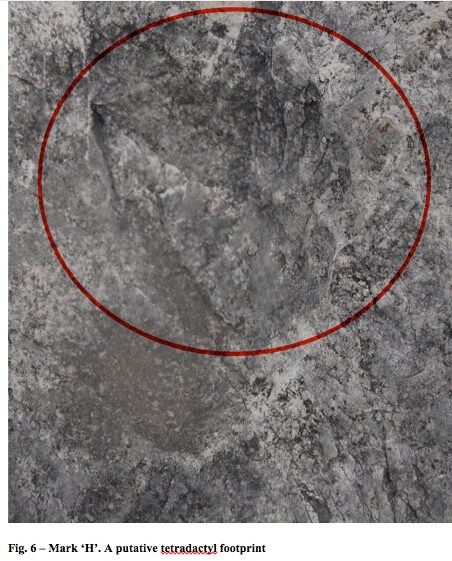

Novellino reiterates that, at this stage, any interpretation of such marks as dinosaur footprints is still speculative. Nevertheless, the presence of a clearly recognizable tetradactyl footprint, with apparent metatarsal traces [figure 6], stands as the most complete ichnological record amongst all other identified marks; this makes the discovery particularly promising. This putative footprint is about 13 cm wide and has an approximate length of 14 cm; all its digits face anteriorly. Its total length, including the putative metatarsal impression, measures about 21 cm. As suggested by Citton in one of his publications, a longer metatarsal trace might indicate a closer resemblance with the osteological structure of theropods rather than with that of ornithopods (dinosaurs having a skeleton very similar to those of birds). In fact, Martin Lockley, a British palaeontologist,had already suggested that ornithopods would leave shorter metatarsal impressions compared to therapods.

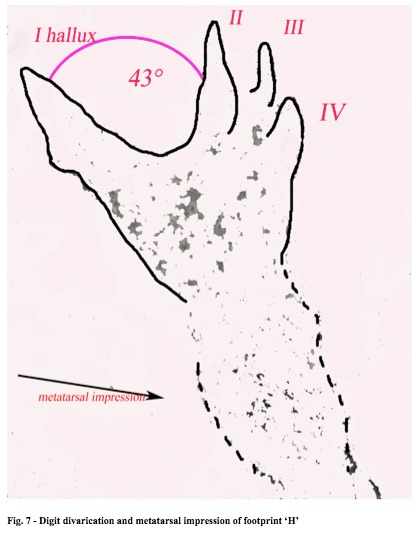

Interestingly enough, specimen ‘H’ has digit II longer than III and IV. Overall, from a merely visual observation of the related photographs, digit IV appears to be shorter and more rounded than II and III. The digit divarication between digit 1 (hallux) and the most protruding digit II is also significant, showing a remarkable angle of approximately 43° [see fig. 7]. All digits appear to have a tendency towards a medium-blunt rather than remarkably sharp tips; claws marks are absent. Overall, at a first glace, this putative footprint, as well as an another one, seems to have a more rounded morphology compared to that of other therapod tracks found in Lazio region and elsewhere. Only further and more detailed analysis might be able to establish whether this footprint is more likely to be associated with a medium/small size therapod or with an ornithopod.

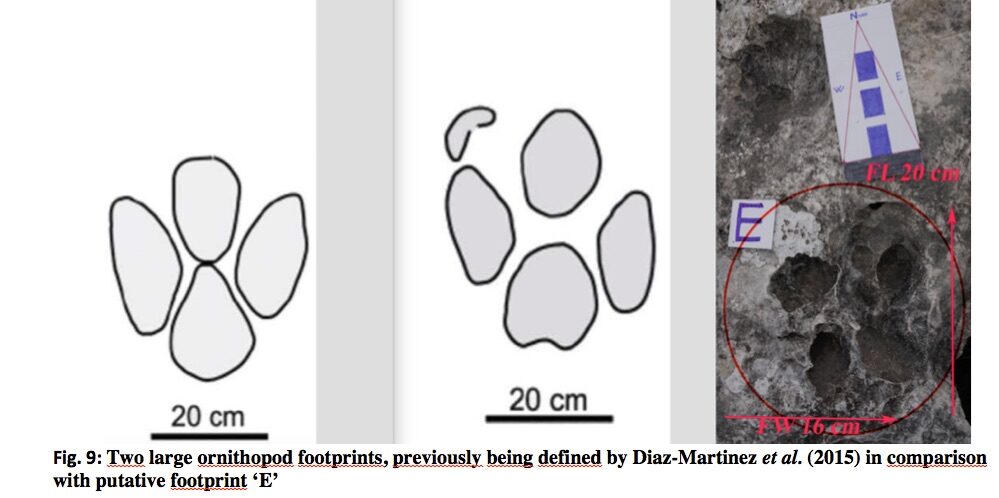

In the proximity of the putative tetradactyl footprint, Novellino also found other semi-circular/semi-elliptical shaped marks [figure 8] bearing some resemblance with those found in the famous ichnosite of Esperia, in 2006, and which largely belong to sauropod dinosaurs. Some of these have the same size, others are smaller or larger, which would suggest that they belonged to specimens of different ages, perhaps of various species and subspecies. Most of these footprints vary between 13 and 18 cm in length and between 9 and 16 cm in width; few of them appear to exhibit finger/nail marks. One particular track ‘E’ [figure 9] has a completely different shape and appears to be similar to two large ornithopod footprints being illustrated by palaeontologist Diaz-Martinez in one of his publications, dated 2015.

According to Novellino, only a few meters away from the first identified track-bearing block thereis a cluster of three oval-shaped marks [figure 10] found on a separate rock. This is being constituted by two almost identical footprints (‘T’ and ‘U’), clearly separated by a mud wall. Below these, there is a more elongated mark.

Novellino is now looking for the assistance of professional palaeontologists willing to carry out a more in-depth assessment of the site. If Novellino’s preliminary findings will be confirmed, this would raise to four the number of ichnosites being discovered in Lazio Region and to two, the number of those identified in the Aurunci Mountains alone.